Welcome to Mythology Mondays, where I highlight a different Greek myth or an aspect of mythology that has influenced the Turning Creek series. The first two books, Lightning in the Dark and Storm in the Mountains are out now.

Since I started writing about my harpies, I have been doing a lot of mythology research. Before starting the Turning Creek series, my mythology knowledge was about what any good English major picks up over years of reading, a decent bit but not encyclopedic. After over a year of reading and writing about Greek mythology, I have come to a conclusion I should have seen coming.

The gender roles in the ancient world were supported by the rigid and degrading roles women were given in the myths told and retold as religion. In modern times, we read them as classic literature.

In Greek mythology, women were allowed to be virgins, whores, or something monstrous. They were never allowed to be beautiful and I would argue that any woman who was not a virgin was made a monster because they believed them to be monstrous.

In this discussion there is always one exception: the goddesses. The goddesses of Greece and Rome were allowed to be virgins, sexual beings, beautiful, ugly, or anything in between. The female gods were allowed to do almost anything without punishment, but if a mortal woman was anything but an ugly virgin, she was punished, and punished harshly.

A woman could not possess beauty or skill. – Beauty was prized by the ancients, but it was reserved for those of royal blood or those who were children of the gods. Likewise, a mortal woman could also never excel at anything if they outshone the the gods. Arachne, who had the misfortune of being a very good weaver, was challenged by Minerva, weaver of the gods. When Arachne was found to be equal in skill to Minerva, the goddess beat her until, shamed, the woman hung herself. Minerva felt remorse over her action and changed the woman into a spider.

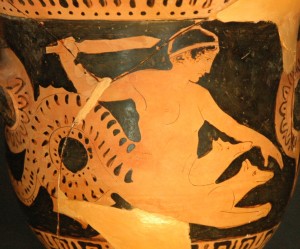

Scylla was a beautiful woman seduced* by Poseidon. She was turned into a hideous beast both for being beautiful and for being seduced. Medea was a beautiful witch that Jason of the Argonauts seduced, married, then abandoned. Medusa was a beautiful mortal who had the misfortune of being seduced by Poseidon in Athena’s temple.

A woman was allowed to be a virgin, at least until one of the philandering gods noticed you and then they seduced you, making you a whore. In a culture where your ability to bear children was the sum of your value, your maidenhead was your ticket to a better life. Unfortunately, this was a ticket easily ripped apart (pun intended), by any man or god who happened to stroll along. Losing your virginity meant you lost your value in society, but if you lost your virtue to the wrong man or god, you were punished. Scylla and Medusa, from the examples above, were turned into hideous creatures by the goddesses who felt betrayed by the rape of the mortal women. The women were punished for the gods’ infidelity.

A woman was allowed to be a whore or a monster. There are many female monsters in Greek mythology, though monsters are not exclusively female. Feminine monsters, of various origins, included Medusa and Scylla (which I have already mentioned), the Sphinx, the Harpies, the Amazons (women who dared to have power and skill, thus they were monsters), the maenads, the Gorgons, and the list goes on and on.

It makes sense that the stories which people told to explain the world were influenced by and supported the beliefs of that culture. Women were not valued. Women, beyond their ability to bear children, had no value and no place in society. There are always exceptions, but I am speaking about the generally accepted views not the exceptions.

Greek Mythology, and other mythology from the ancient world, reflected the idea that women were virgins until they were desired by a man and then they were taken. After they had been used, they were no longer of value, they were monstrous, both physically and spiritually.

This has implications for us today as we consider how the ancients myths have woven their way into the vernacular of our modern culture. Using an example above, we remember Medea as a witch who killed her children and Jason as a virtuous hero. We do not remember this couple as they were in the myths: Medea as a desperate and abandoned woman and Jason as a narcissistic adulterer.

As I learn more about ancient myths, I have been reminded to look at the stories critically with a modern lens that is sensitive to the culture which created them. They are stories of greed, betrayal, jealousy, desire, love, anguish, and life. We are all capable of any or all of these emotions. Perhaps the thing we should learn most from the ancient myths is temperance.

*Seduced in the ancient writings is a gentle way of saying the god didn’t take no for an answer and raped her.

![By Ad Meskens; sculpture Antonio Canova (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://wanderingeyre.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Metropolitan_canova_perseus_medusa_02.jpg)